Interview with UNC Charlotte prof. Emek Ergun and her co-editor on major new book

Feminist Translation Studies: Local and Transnational Perspectives (Routledge, 2017) explores feminist approaches to translation across diverse geographical and historical locations as resistant transnational practices that challenge multiple forms of domination. In the piece, they introduce feminist translation studies, discuss the role that translation plays in the transnational, and examine the relationship between feminist praxis, translation, and activism.

Q: You describe the collection as emerging ‘at a historical moment of geopolitical and inter/disciplinary growth’ for feminist translation studies. Could you introduce feminist translation? When did it begin and how has it evolved to date?

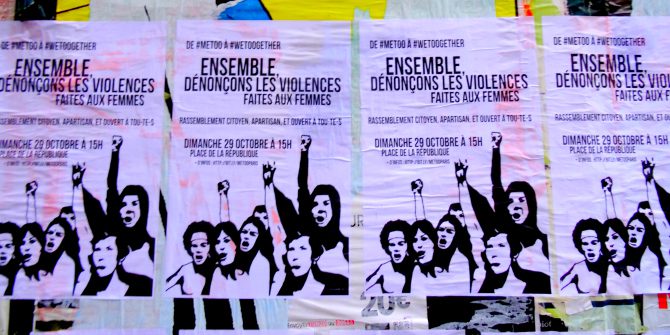

If we accept that feminism, as a sociopolitical struggle aimed at challenging and disrupting gender power relations (as well as other relations of power that intersect with gender), is an approach to absolutely any and every aspect of our lives, then feminist translation is a political meaning-making praxis that challenges hegemonic power relations in any and every aspect of translation. This feminist perspective to translation involves identifying where different mechanisms of gender discrimination lie in translation and disclosing the ideological values behind them, as a first step to proposing alternatives for gender equality. Feminist translation could be defined as any conscious discursive intervention that seeks to contribute, through translation, to global social justice.

When trying to set the origins of feminist translation, there seems to be academic consensus in referring to the theories and textual practices developed in bilingual Quebec, Canada, by a group of translators and translation scholars in the 1970s and 1980s. They were indeed first in openly self-claiming the label ‘feminist translation’ to describe their efforts to incorporate feminist values into their avant-garde and experimental literary translation projects. However, we argue that other theories and practices of feminist translation had emerged long before and in other geographies, even if they were not self-proclaimed as such – examples include Margaret Tyler, Aphra Behn, Julia E. Smith, and Lucy Cady Stanton, to name just a few.

In early feminist translation scholarship, the emphasis was mainly placed on studying linguistic aspects of translation (how gender is represented in different languages and the challenges that poses to translation) and on doing comparative textual analyses of women-authored literature and feminist philosophical texts. But feminist translation has been rapidly evolving, and it now welcomes new interdisciplinary encounters with, for example, audio-visual translation, machine translation, queer translation, interpreting, and, more recently, social media translation. It has also expanded its geopolitical scope, which we explain later.

Q: You take care to make a distinction between studies that look at ‘gender and translation’ or ‘women and translation’ and feminist translation. What is crucial about this difference?

Feminism is a political term: it puts the emphasis on activism to dismantle power relations and to change the world. As a political praxis and a field of enquiry, feminism analyses how gender relations are structured in society to reveal the ways in which women, as a social group, have been and still are systematically discriminated against – while acknowledging that women is not a unitary category and adopting an intersectional approach to pay attention to differences and inequalities among women across the globe…